SerenityOS Code Tour: The Serenity USB Stack, Part 1

USB is one of those things that many people are afraid to touch. In fact, for quite some time, it was one of the few buses that nobody had even dared utter mention to in the Serenity IRC, even though the Kernel was somewhat fleshed out and could easily support a Host Controller Device. The main issue is the sheer volume of software to even get a device enumerated (A word that will be explained further down in this post).

This post will go into some detail as to the design of the SerenityOS USB Stack, Host Controller Driver, and support software enough that anybody interested in getting started with USB can jump right into the code without feeling intimidated by words such as “enumerate”, “host controller”, “frame” and so on and so forth.

To alleviate pressure on myself and you, I’m going to split this into multiple parts that goes into USB (and how we implement in Serenity) step by step. Part 1 (this document) will describe what USB is, and how we implement the USB Driver to opaquely interface with any Host Controller driver that’s implemented on the system.

What is USB?

First, we should start of by understanding what USB is. As most people reading this probably already know, USB is an acronym that stands for “Universal Serial Bus”. In the 80’s and 90’s, Computers were plagued by a situation where you could have multiple devices that used different buses. Your printer uses the Parallel port, your mouse uses the Serial port, and your motherboard has this funny little connector that you haven’t quite worked out what it exactly does, but hey, Windows loads a driver for it anyway, so it must do something. In an effort to constrain this problem as computers became more and more mainstream, a few different manufacturers and Software Companies, such as Compaq, Microsoft, IBM and DEC (to name a few), came together to make connectivity to a PC a much friendlier experience for the end user. After 20+ years, it’s safe to say that the design has held pretty well, as today even Video is streamed over USB on some devices.

How does USB work?

Physical Layer

On a more technical level, USB is a differential serial signal. This means that a single “bit” is actually two wires, where the output is the subtraction of the two Data signals, similar to the CAN bus used in automobiles. If you’ve ever looked at the mouth of a Male USB cable, this is why you’ll see four pins instead of three; the middle two pins are D+ and D-. There are two 15kΩ weak pull-down resistors on the Host end, and one or two 15kΩ pull-up resistors on the device end, which is how USB differentiates the speed of the device you’ve connected. I won’t go too much further into the electrical characteristics of USB, as it’s a bit of a bog, but if you’re interested you can find the technical information for this on Wikipedia.

Logical Layer

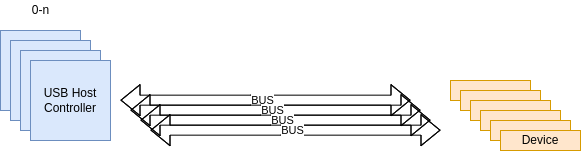

At a logical level, the USB is split into two parts: The Host (your computer) and the Device (the thing you’ve plugged into your computer). The host requires some kind of special hardare (called the Host Controller) to manage USB transactions, as the frame format and whatnot isn’t as simple as just blasting out bits over the wire as, say, your serial or parallel port. This device, also called the “Host Controller”, is the part that the Kernel manages that deals with scheduling transers, controlling the ports etc. In essence, it’s the interface by which we, the SuperCool(TM) Kernel Developers, can send and receive data to the different devices connected to the bus, with the correct electrical characteristics (such as timings and stuffing bits) done for free by the silicon without a need for Programmer intervention (which would be very messy). Below is a diagram of a typical configuration:

As you can see, a single machine can have more than one Host Controller, and hence more than one Bus. In fact, by running lsusb (on any *nix Operating System) you can usually observe the following:

Bus 009 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Bus 010 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0003 Linux Foundation 3.0 root hub

Bus 008 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0003 Linux Foundation 3.0 root hub

Bus 007 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Bus 006 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0003 Linux Foundation 3.0 root hub

Bus 005 Device 003: ID 045e:082a Microsoft Corp. Microsoft Pro Intellimouse

Bus 005 Device 002: ID 04b4:0510 Cypress Semiconductor Corp. HID Keyboard

Bus 005 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Bus 004 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0003 Linux Foundation 3.0 root hub

Bus 003 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Bus 002 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0003 Linux Foundation 3.0 root hub

Bus 001 Device 003: ID 1397:0509 BEHRINGER International GmbH UMC404HD 192k

Bus 001 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Notice how the different devices are connected to different buses? Each Controller might only support up to 4 devices, so it’s necessary to have more than a few controllers to support the amount of USB ports you have on your computer.

But how does the host controller know where to send the data? And what is this data? There are obviously multiple devices connected to a single bus, so how do we not end up with a collision? That’s done via a process called “enumeration”. Before that, however, let’s take a look at some of the basic structures that composes USB at a Software Level,

USB Descriptors

The fundamental building block of a USB device is the Descriptor. These descriptors, as outlined in the USB specification, describe different parts of the USB device in question and allow us to configure it how we’d like, or get information about the device to the user.

- Device Descriptor: Describes some physical properties about the device, how big a packet is, the device’s Product and Vendor ID, etc. There is only one Device Descriptor on a USB device

- Configuration Descriptor: Describes how the device can be configured, such as maximum power, attributes (about power) and how many interfaces there are for that configuration.

- Interface Descriptor: Describes a group of endpopints (connected via

Pipes) into a logical bundle, which becomes a single feature (the camera or microphone in your USB webcam, for instance, would be separate interfaces). - Endpoint Descriptor: Describes the Endpoint (aka buffer) on the device that a

Pipeis connected to. It tells us what type of endpoint it is (i.e how we should transfer the data), the data direction (Endpoints cannot be both, besides the default Endpoint and Pipe) etc. Basically any information required to pull data to/from the device from/to the Host.

For the sake of brevity, I won’t go into detail about these here. You can read more about them at USB in a Nutshell.

Software Architecture

Fundamentally, there are three Software layers to USB:

- The Host Controller Driver

- The USB Driver

- The Device Driver

Parts 1. and 2. are managed by the Kernel directly in Kernel space. The Host Controller driver, as you probably expect, defines an API for us to schedule packets on the actual host controller driver, and has a series of registers that we must write to. The USB Driver acts more like a service that defines logical constructs, such as a a Pipe, Hub and Device. The most important of these constructs is the Pipe.

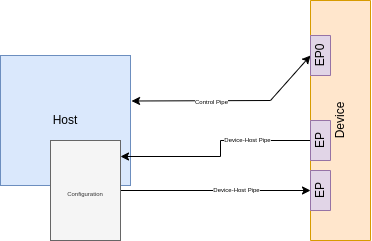

A pipe is very simple construct. In essence, there are two buffers for data, the buffer on your computer (in physical memory) and the buffer on the device. You can think about it like using two tin cans and a string, with you on one end and your friend on the other end. You have a direct connection to each other, where the buffers are your brains and the endpoints your mouths. Your friend, from your perspective, is what’s known as an Endpoint. It looks something like this:

As you can see, the Host always has an In/Out connection to Endpoint0 (the “Default Pipe”) which is required for device enumeration, as well as an Input Pipe and an Output Pipe to a configuration. When a transfer is started, you’d specify the Address of the endpoint you want to write to or read from when you construct your USB packet. Serenity currently doesn’t support

The Serenity USB Stack

So enough about USB. “Where’s the code? That’s why I’m here, Quaker!” I can hear you yelling from behind your monitor. Okay, okay, sorry. I had to condense down 12+ months of research for you into a few paragraphs that Ali and Brian proofread for me. Cut me some slack!

Serenity’s USB stack directly implements USB structures in a way that you would expect from reading the above:

- The

Device(/Kernel/Bus/USB/USBDevice.h) class contains aNonnullRefptr<>to a defaultPipe, a Vendor and Product ID, aNonnullRefPtrto the controller it exists on, and its’ address (amongst other things) - The

Pipe(/Kernel/Bus/USB/USBPipe.h) class contains a the endpoint address, the address of the device it’s connected to, it’s poll interval and the maximum packet size of the device. It creates transfers on a transfer-by-transfer basis - T

Transfer(/Kernel/Bus/USB/USBTransfer.h) class contains a Physical Memory Buffer that we request from the Kernel at the time of transfer, a reference to the pipe who created it, and some flags we propagate back up through the stack.

And that’s it. Those are the three structures you need to get some level of USB working (outside of the Host Controller driver itself, which will be discussed another time). Putting it together we have the following:

- When a device is connected, the Kernel allocates a new

Devicestructure. - It then (automatically) constructs the default

Pipe, as it cannot be anullptr, via the constructor. - We then do a

Control Transferon the Default Pipe. Each transfer is created as we need it. - The

Transferstructure allocates a physical page in the kernel for us to write into. - The Transfer’s buffer is split into multiple, controller sized packets in the Host Controller driver and sent out over the wire to the device.

Device Enumeration

So by now, you know some pretty fundamental basics of USB; how the devices are connected, what a “Host Controller” is amongst other things, but how does this all fit together? Well, the genesis of any USB connectivity is through device enumeration. Every device on a single USB bus requires a unique identifier that is assigned to it at runtime. This is the Device’s ID on the bus. Whenever we start a transfer, we put the Device ID into the packet, and the corresponding device will put its’ hand up and go “that’s me!” and respond to the request we have made to it. There is a special case for this, however. The USB specification states that any device that has yet to be assigned a unique ID must respond to address 0. With that knowledge in hand, here’s how enumeration works:

- A device is plugged into the system.

- We read the first 8-bytes of the Device Descriptor, as this contains the number of bytes of the full descriptor, and the max packet size supported by the device.

- The max packet type is set for future transfers.

- We read in the entire Device Descriptor.

- We allocate a new, unused address for this bus.

- We send a

SET_ADDRESSpacket to the device, informing it that the host now considers it devicen. - The device descriptor is cached for later retrieval in

/sys/bus/usbfor programs likelsusb.

In Serenity, this is performed by the following function in USB::Device:

ErrorOr<void> Device::enumerate_device()

{

USBDeviceDescriptor dev_descriptor {};

// Send 8-bytes to get at least the `max_packet_size` from the device

constexpr u8 short_device_descriptor_length = 8;

auto transfer_length = TRY(m_default_pipe->control_transfer(USB_REQUEST_TRANSFER_DIRECTION_DEVICE_TO_HOST, USB_REQUEST_GET_DESCRIPTOR, (DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_DEVICE << 8), 0, short_device_descriptor_length, &dev_descriptor));

// FIXME: This be "not equal to" instead of "less than", but control transfers report a higher transfer length than expected.

if (transfer_length < short_device_descriptor_length) {

dbgln("USB Device: Not enough bytes for short device descriptor. Expected {}, got {}.", short_device_descriptor_length, transfer_length);

return EIO;

}

// Ensure that this is actually a valid device descriptor...

VERIFY(dev_descriptor.descriptor_header.descriptor_type == DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_DEVICE);

m_default_pipe->set_max_packet_size(dev_descriptor.max_packet_size);

transfer_length = TRY(m_default_pipe->control_transfer(USB_REQUEST_TRANSFER_DIRECTION_DEVICE_TO_HOST, USB_REQUEST_GET_DESCRIPTOR, (DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_DEVICE << 8), 0, sizeof(USBDeviceDescriptor), &dev_descriptor));

// FIXME: This be "not equal to" instead of "less than", but control transfers report a higher transfer length than expected.

if (transfer_length < sizeof(USBDeviceDescriptor)) {

dbgln("USB Device: Unexpected device descriptor length. Expected {}, got {}.", sizeof(USBDeviceDescriptor), transfer_length);

return EIO;

}

auto new_address = m_controller->allocate_address();

// Attempt to set devices address on the bus

transfer_length = TRY(m_default_pipe->control_transfer(USB_REQUEST_TRANSFER_DIRECTION_HOST_TO_DEVICE, USB_REQUEST_SET_ADDRESS, new_address, 0, 0, nullptr));

// This has to be set after we send out the "Set Address" request because it might be sent to the root hub.

// The root hub uses the address to intercept requests to itself.

m_address = new_address;

m_default_pipe->set_device_address(new_address);

dbgln_if(USB_DEBUG, "USB Device: Set address to {}", m_address);

memcpy(&m_device_descriptor, &dev_descriptor, sizeof(USBDeviceDescriptor));

return {};

}